AFRO-AMERICAN MUSIC INSTITUTE CELEBRATES 36 YEARS

http://www.indiegogo.com/projects/building-today-for-tomorrow/x/267428

Pain Relief Beyond Belief

http://www.komehsaessentials.com/

PITTSBURGH JAZZ

From Blakey to Brown, Como to Costa, Eckstine to Eldridge, Galbraith to Garner, Harris to Hines, Horne to Hyman, Jamal to Jefferson, Kelly to Klook; Mancini to Marmarosa, May to Mitchell, Negri to Nestico, Parlan to Ponder, Reed to Ruther, Strayhorn to Sullivan, Turk to Turrentine, Wade to Williams… the forthcoming publication Treasury of Pittsburgh Jazz Connections by Dr. Nelson Harrison and Dr. Ralph Proctor, Jr. will document the legacy of one of the world’s greatest jazz capitals.

Do you want to know who Dizzy Gillespie idolized? Did you ever wonder who inspired Kenny Clarke and Art Blakey? Who was the pianist that mentored Monk, Bud Powell, Tad Dameron, Elmo Hope, Sarah Vaughan and Mel Torme? Who was Art Tatum’s idol and Nat Cole’s mentor? What musical quartet pioneered the concept adopted later by the Modern Jazz Quartet? Were you ever curious to know who taught saxophone to Stanley Turrentine or who taught piano to Ahmad Jamal? What community music school trained Robert McFerrin, Sr. for his history-making debut with the Metropolitan Opera? What virtually unknown pianist was a significant influence on young John Coltrane, Shirley Scott, McCoy Tyner, Bobby Timmons and Ray Bryant when he moved to Philadelphia from Pittsburgh in the 1940s? Would you be surprised to know that Erroll Garner attended classes at the Julliard School of Music in New York and was at the top of his class in writing and arranging proficiency?

Some answers can be gleaned from the postings on the Pittsburgh Jazz Network.

For almost 100 years the Pittsburgh region has been a metacenter of jazz originality that is second to no other in the history of jazz. One of the best kept secrets in jazz folklore, the Pittsburgh Jazz Legacy has heretofore remained mythical. We have dubbed it “the greatest story never told” since it has not been represented in writing before now in such a way as to be accessible to anyone seeking to know more about it. When it was happening, little did we know how priceless the memories would become when the times were gone.

Today jazz is still king in Pittsburgh, with events, performances and activities happening all the time. The Pittsburgh Jazz Network is dedicated to celebrating and showcasing the places, artists and fans that carry on the legacy of Pittsburgh's jazz heritage.

WELCOME!

Groups

Duke Ellington is first African-American and the first musician to solo on U.S. circulating coin

MARY LOU WILLIAMS

Pittsburgh's historic black musicians' union to be honored this weekend

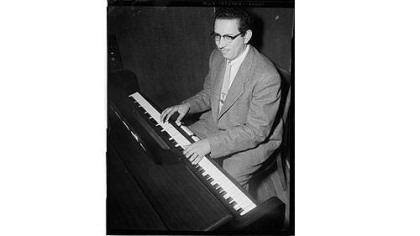

George "Duke" Spaulding rarely smiles at the keyboard.

Not when he and the rest of the Leroy Brown Orchestra were mainstays of the Hill District jazz scene in the 1940s, '50s and '60s. Not when he tuned pianos for Liberace, the Civic Light Opera and the Mellon family. And not today when he coaxes from his electric piano the chords of "Come Sunday" by his nicknamesake, Duke Ellington, "Take the 'A' Train" by Pittsburgh native Billy Strayhorn and "How Firm a Foundation," a hymn requested by his daughter, Simone Spaulding Cephas.

Smiling "ain't what you're paying me for" was his usual answer to those wondering why someone who played with such joy looked so dour.

With or without a smile, the Wilkinsburg man always gives plenty of what he is paid for, and he knows he can thank Local 471 for making sure he was paid the going rate, even if it was less than what white musicians made.

At 7 p.m. today and 11:30 a.m. Saturday, Mr. Spaulding, 89, will take part in a panel discussion and plaque dedication, respectively, honoring the African-American musicians' union. From 1908 until 1966, when it merged with the all-white Local 60 of the American Federation of Musicians, Local 471 worked on behalf of black musicians and battled strict yet unwritten rules that limited their performances to the Hill and other black neighborhoods in and around Pittsburgh.

Mr. Spaulding notes with pride that Leroy Brown's band was the first black band to play regularly at the Hollywood Show Bar on Sixth Street in 1945. But that was the exception. More common was what happened when another band had a contract to play at a different Downtown club.

"The white musicians' union got the bartenders to picket outside," he said, adding that his band was not allowed to perform.

The boundary was Grant Street: Black bands could play at establishments above Grant and in parts of the North Side, Homewood and Wilkinsburg. Most other dance halls, clubs, parties, etc., were the domain of the white musicians' union.

On Saturday, members of the African American Jazz Preservation Society will unveil a state historical plaque at Crawford Street between Wylie and Webster avenues. Near that spot, the union's Musicians Club was the syncopated heartbeat of Pittsburgh's jazz community, drawing together younger musicians like Ahmad Jamal and George Benson, national headliners like Dizzy Gillespie, Ben Webster and Cab Calloway and veteran local pros like Mr. Spaulding and Charles "Chuck" Austin for early-morning jam sessions that electrified music lovers, black and white.

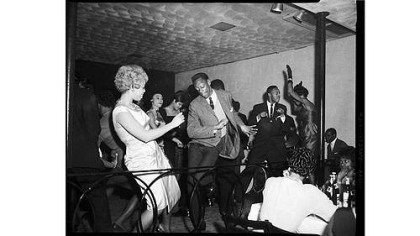

Much of Local 471's influence came through its Musicians Club, where union members, visiting performers and jazz lovers who paid dues as associate members gathered to drink and eat in the bar and restaurant on the first floor. Bands performed on stages on the first and second floors and jam sessions began around 2 a.m.

Drummer Curtis Young said jazz performers and their fans found safe haven in clubs like this one: "People would get right off work, wouldn't even change clothes, and come to the clubs to simply hear good music, dance and feel good about themselves. ... As musicians, we just wanted to offer a good time and enjoy ourselves in the process," he told writer Shakura Sabur.

In the Hill District and other predominantly black neighborhoods, the union protected its members by confronting and, in some cases, pulling off the bandstand performers who weren't dues-paying members. The camaraderie between bandmates grew to include other black musicians who were paid $50 to $60 for four or five hours of work.

Mr. Spaulding, an Asheville, N.C., native who was not yet 20 but already a professional musician when he moved to Pittsburgh in 1941, said older musicians helped younger ones. Teenagers sometimes cut school or sneaked out of their homes at night to perform with their elders at the Musicians Club. And even seasoned veterans could improve their "chops" jamming with nationally known musicians.

Black headliners like Art Tatum and Stanley Turrentine could play the big hotels Downtown. but they weren't allowed to stay overnight there or eat in most restaurants. When they needed a quick alteration on a tuxedo or someplace to shower, they turned to Local 471 members for help and advice.

Some of those headliners were from Pittsburgh. Jazz greats such as Earl "Fatha" Hines, Maxine Sullivan, Roy Eldridge and Mary Lou Williams had to leave the city to make it big, Mr. Spaulding said.

"You couldn't make a living in Pittsburgh as a musician," he said.

So he and others worked day jobs. For more than 40 years, he was a technician and tuner for Baldwin Piano Co. He's also a long-standing member of the American Guild of Organists and still performs occasionally in local churches.

Ms. Spaulding Cephas, 61, of Wilkinsburg, one of Mr. Spaulding's six children, calls herself his roadie.

"I try not to brag about my Dad ... but when God touches you..."

Panel discussions on the role of black musicians' unions will be held at 7 p.m. today at the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, 810 Penn Ave., and at 1 p.m. Saturday in the Hillman Auditorium at the Hill House Association, 1835 Centre Ave., Hill District.

First Published June 22, 2012 12:02 am

Read more: http://www.post-gazette.com/stories/ae/music/a-legend-bares-his-tee...

Comment

-

Comment by SOUTHSIDE JERRY MELLIX on June 23, 2012 at 2:46pm

-

George, I always called him DUKE, and I have known of each other for over 40 years. I'm happy that his history is being noted!

-

Comment by Dr. Nelson Harrison on June 23, 2012 at 12:36pm

-

-

Comment by Dr. Nelson Harrison on June 23, 2012 at 12:35pm

-

-

Comment by Dr. Nelson Harrison on June 23, 2012 at 12:34pm

-

-

Comment by Dr. Nelson Harrison on June 23, 2012 at 12:32pm

-

© 2025 Created by Dr. Nelson Harrison.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of Pittsburgh Jazz Network to add comments!

Join Pittsburgh Jazz Network