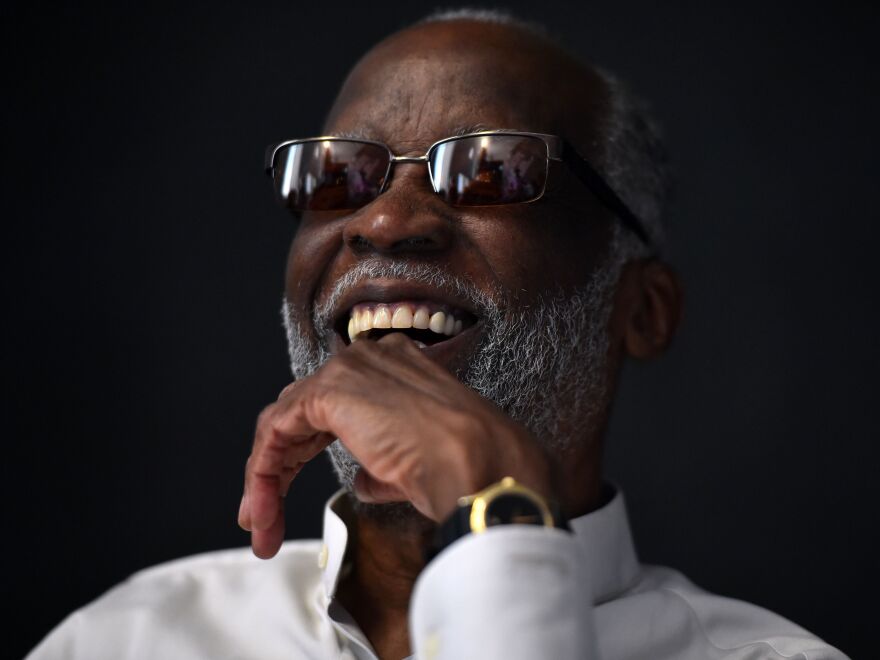

Ahmad Jamal, whose taut, spare and rhythmically supple approach to jazz piano influenced generations of other musicians who embraced his less-is-more dynamics, died April 16 at his home in Ashley Falls, Mass. He was 92.

Ahmad Jamal, the influential jazz pianist, composer and band leader, has died at the age of 92.

His daughter, Sumayah Jamal, confirmed to the New York Times that the cause of death was prostate cancer.

Embarking on a professional music career from the age of 14, over seven decades Jamal forged a unique sound that leapt over genre boundaries. Minimalism, classical, modernism, pop: Ahmad was sometimes likened to Thelonious Monk in terms of his ability to innovate and influence other musicians: his piano would be sampled by the likes of De La Soul, Jay-Z, Common and Nas. The trumpeter Miles Davis once said: “All my inspiration comes from Ahmad Jamal,” writing in his memoir that his friend had “knocked me out with his concept of space, his lightness of touch, and the way he phrases notes and chords and passages”.

Born Frederick Russell Jones in Pittsburgh in 1930, Jamal began playing music at three when an uncle challenged him to copy him on the family piano. He devoured “reams of sheet music” in all genres donated by his aunt and began receiving formal training when he was seven, then was composing at the age of 10. He found himself drawn to works by the French classical composers Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy. By his early teens he was performing in nightclubs. “I’d do algebra during intermission, between sets,” he once told Down Beat magazine.

After marrying, he settled in Chicago in 1950 and converted to Islam from the Baptist faith of his family, becoming one of the first African American performers to publicly speak of his Muslim faith. Talking to Time magazine about going by the name Ahmad Jamal, he said: “I haven’t adopted a name. It’s a part of my ancestral background and heritage. I have re-established my original name. I have gone back to my own vine and fig tree.”

Jamal performed jazz, which he called “American classical music” all his life, in the house band for Chicago’s Pershing Hotel lounge – a Black-owned favourite of the likes of Sammy Davis Jr and Billie Holiday, and where he recorded his 1958 breakthrough album, Ahmad Jamal at the Pershing: But Not For Me. The album sold 1m copies and remained on the Billboard magazine charts for more than 100 weeks, making Jamal a household name when rock’n’roll was on the up and jazz was beginning to wane.

He and his always-rotating lineup continued performing in nightclubs across the US to devoted audiences: Jamal bought a mansion and started his own nightclub, the Alhambra (which served no alcohol, as per his religious beliefs): the club was one in a series of unsuccessful business ventures that eventually left him saddled with debt.

His first marriage ended in divorce in 1962 and he was hospitalised in 1963 after an apparent overdose. He didn’t resume touring and recording until 1964, having moved to New York for a long residency at the Village Gate nightclub.

His keyboard version of the theme from M*A*S*H was critically acclaimed in 1970 and was followed by another significant album, The Awakening, with the bassist Jamil Nasser and the drummer Frank Gant.

“I used to do 20% my own pieces and 80% other people’s; now it’s turned the other way,” he told the Guardian in 2013. “After a certain time you discover the Mozart in you, the Duke Ellington or Billy Strayhorn in you. It takes time to discover yourself. You also have to find and keep players who are in tune with what you’re doing; you have that empathy, the quality of breathing together.”

In the 1980s and 90s, Jamal continued to perform relentlessly and released several live albums, shoring up his reputation as one of the best living jazz performers. He was named Jazz Master in 1994 by the National Endowment for the Arts and won a lifetime achievement Grammy in 2017.

His first daughter Mumeenah Counts died in 1979. He is survived by his third ex-wife and manager, Laura Hess-Hay; Sumayah, his daughter with his second ex-wife; and two grandchildren.

Speaking about his ability to continue performing and touring in his 80s, he told the Guardian: “It’s a divine gift, that’s all I can tell you. We don’t create, we discover – and the process of discovery gives you energy … Rhythm is very important in music, and your life has to have rhythms too.

“You can exercise properly, eat properly – but the most important thing of all is thinking properly. Things are in a mess, and that’s an understatement; so much is being lost because of greed.

“There are very few authentic, pure approaches to life now. But this music is one of them, and it continues to be.”