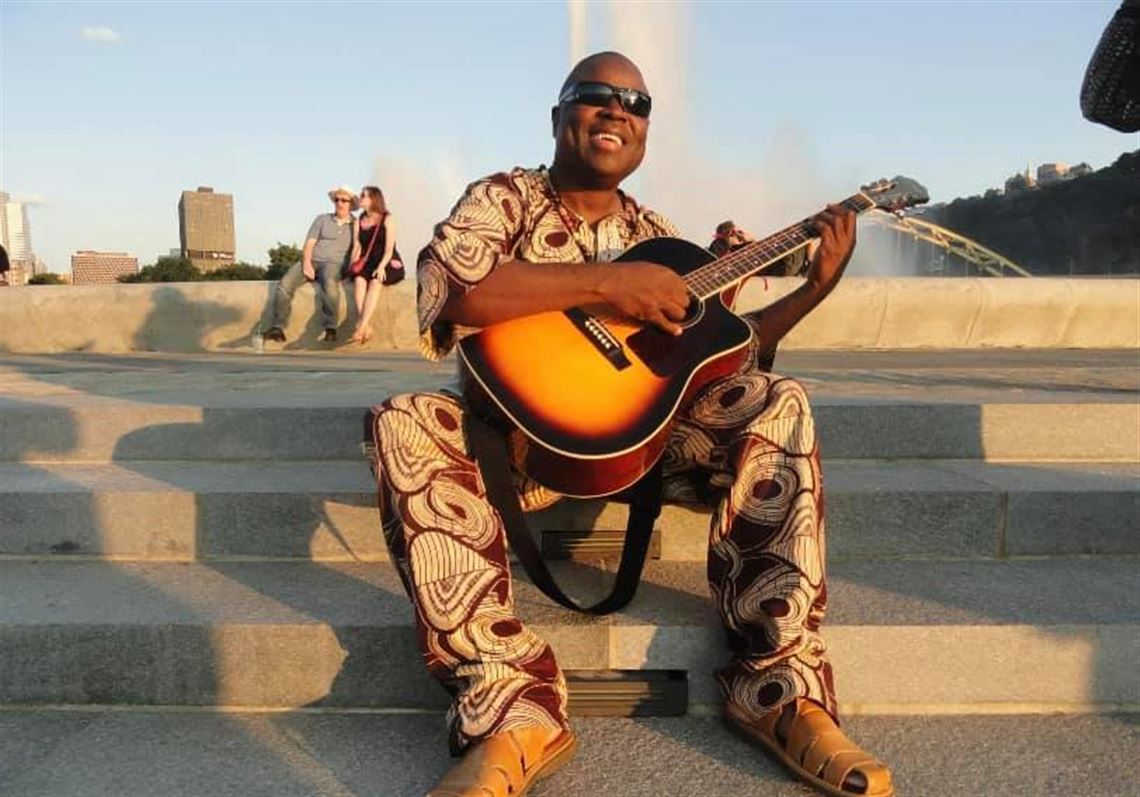

Pittsburgh became a more rhythmic, expansive and worldly place — overnight — when Anicet Mundundu settled here in 1990.

The Congo native was a respected multi-instrumentalist, scholar and producer who was involved in or led such groups as the Pitt African Drumming Ensemble, Jambo Lugamba, Umoja African Arts, Afrika Yetu and Wacongo Dance Company.

Mr. Mundundu wasn’t the typical multi-instrumentalist who played related instruments. He was proficient in drums, percussion, guitar, keyboards and saxophone, along with being a powerful vocalist.

The Highland Park resident, who died on Nov. 26 from complications of pneumonia at 62, received his B.A. in music education from the Institut National des Arts of the Université Nationale du Zaire and was the director of the GEVAKIN choir of Kinshasa, Congo.

When the choir toured here, without him, in 1989, his cousin, Oba Elie Kihonia, settled in Pittsburgh and co-founded Umoja African Arts Company. He urged Mr. Mundundu to join him here, he says, “we knew we needed him here, because there were not many scholars.”

He considered Mr. Mundundu to be the rare case of an academic who was also a great performer and musician.

A year later, he settled here with his wife Ruth to earn his master’s and doctorate in the ethnomusicology department at the University of Pittsburgh, where he also taught music fundamentals, piano, world music and music technology, and directed the African Drumming Ensemble.

Among his students was Dino Lopreiato, who would later become the drummer for the band Chaibaba and Mr. Mundundu’s collaborator in the African Drumming Ensemble and a soukous side project. He met the Congolese musician in 1991 when he signed up for the African drumming class at Pitt.

“When I got to Pitt,” Mr. Lopreiato said, “I wasn't able to have a drum set near me to practice, so my adviser said, ‘Well, you should look into this class.’ As soon as I went in, Anicet was very welcoming. He would teach everything from the very beginning: how to hold the drum, different ways to make sounds come out of the drum because most players would just bang the drum. He showed us the many tones that come out. And then he would teach you songs, all in African.”

Music aside, the popularity of Mr. Mundundu’s classes was also a factor of his patience and good cheer.

“He never ever made anybody feel like they weren't good enough or they couldn't play something that they couldn't do,” Mr. Lopreiato said. “He was always able to find a part for them, and he would actually push that person to do better.”

Together, they turned the African Drumming Ensemble, which had existed since 1983, into an organization in the early ‘90s so they would have funding to acquire instruments and stage bigger performances. The ensemble grew from a half-dozen to as many as 25 players.

“We would take the drum ensemble to places he never played, like Club Cafe, and people were amazed by the music and how good and how incredible it sounded,” Mr. Lopreiato said. “He also was very good at interacting with the audience, doing little jokes and getting everyone involved.”

Mr. Lopreiato’s Chaibaba bandmate Ketan Bakrania came to Pitt in the early ’90s as an art major who was into metal, and discovered a whole new world in the drumming class.

“I’m an Indian,” said Mr. Bakrania. “I was born in Uganda. But the Indians were kicked out by the military leader Idi Amin in ‘72. I was only six months old when I left Africa, but when I came to Pitt and discovered that class, I couldn’t help the feeling of ‘Oh, the Africans found me!’ ”

However, in the best of ways.

“His presence and energy, he was really welcoming and very open and very joyful. At the same time, if you could imagine, he had the firepower on top of that.”

Mr. Mundundu’s collaborations included work with saxophonist Nathan Davis, with Kuntu Repertory Theater on “Sarafina” and with such local institutions as Pittsburgh Ballet Theater, Pittsburgh Symphony’s Pops and River City Brass Band. He and Ruth, who worked for a catering company specializing in African foods, also presented African food and music events.

With Mr. Kihonia, he formed Afrika Yetu to be a production company for African arts.

“With Umoja we were following the school curriculum,” he says, “but we felt it was important to have our stamp, our own voice.”

In the early ’00s, Mr. Mundundu challenged his two Chaibaba students to join him in an Afropop project that required them to practically relearn their instruments.

“It was some of the most difficult music I ever played,” Mr. Lopreiato said, “because the way of thinking on the drums was totally different. The beats weren’t where I thought they were. But Anicet would call for me a bunch of collaborations and it was always like, ‘Oh yeah, I’ll play. If you’re doing it, I’ll be there.’ ”

“Anicet really touched a lot of lives,” he said. “Real music can do that.”

That work is not done, according to Mr. Kihonia, who was calling from Congo, where they just held a tribute to his cousin.

He says there are hundreds of recordings and some scholarly works that Mr. Mundundo was not able to publish because of his immigration status.

“I will make sure it is published,” he says.

Mr. Mundundu is survived by his wife, Ruth, and son, Anicet Mundundu Jr. There will be a viewing at House of Paradise, 608 E. Warrington Ave., Allentown, from 2-4 and 6-8 p.m. Friday, and a funeral at House of Transformation, 623 Main St., Elliott, at 11 a.m. Saturday.

First Published December 1, 2020, 12:30pm