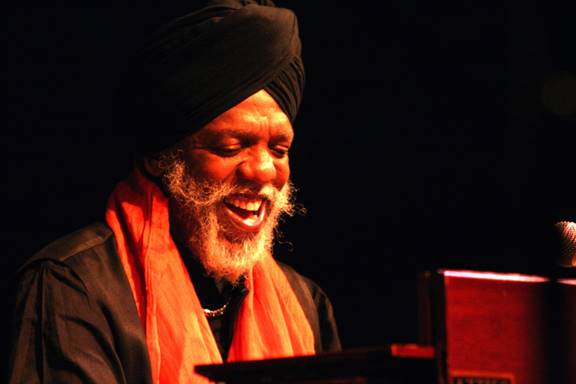

Dr. Lonnie Smith at the 2013 TD Toronto Jazz Festival (photo: Kris King)

Dr. Lonnie Smith at the 2013 TD Toronto Jazz Festival (photo: Kris King)Dr. Lonnie Smith, a Hammond B-3 organist who was a major stylist in the realm of soul jazz—and, later, one of the architects of acid jazz—died September 28 at his home in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. He was 79.

His death was announced in a statement by his label, Blue Note Records. Cause of death was pulmonary fibrosis.

A native of Buffalo, New York, Smith converted the organ grooves of his primary influence, Jimmy Smith, into a unique, genre-busting style. Early recordings with George Benson and Lou Donaldson incorporated his love of R&B; in later years he embraced darker funk, fusion, and psychedelia and collaborated with a host of unusual musical partners, from the Roots to Iggy Pop. His music became a foundation (by way of sampling) of the acid-jazz movement of the early 1990s, sparking a renaissance in a career that had then lain dormant for a decade.

Smith’s distinctive music was paralleled by a distinctive persona. Though he was known affectionately as “Doc,” the “doctor” honorific in Smith’s name was an invention of his own (in part to avoid confusion with his fellow keyboardist Lonnie Liston Smith). His trademark was a turban, which he adopted in the mid-1970s; reports in some corners said that Smith had become a Sikh, while others insisted that the new headgear was purely an affectation. Smith declined to answer questions about it. However, WBGO radio’s Greg Bryant, who had previously worked with Smith, has said that he wore the turban “as a symbol of universal spirituality, love and respect.”

The more mysterious aspects of his presentation were offset by his playful demeanor—rather than a shadowy enigma, the Doc simply enjoyed messing with you. This writer interviewed him in 2012, two days after his 70th birthday; when I wished him a belated happy birthday, he gave me a confused look and said, “Not my birthday!” When I pressed the point that yes, he had just turned 70, he leaned into me and whispered, “That’s a fallacy.”

Dr. B3: The Soul of the Music, a crowdfunded documentary on Smith’s life and music, was produced earlier this year.

Lonnie Smith was born July 3, 1942 in Lackawanna, New York, just south of Buffalo. His mother was his earliest musical influence, a music lover who sang around the house and exposed her son to jazz, classical, and especially gospel music. Smith himself began as a vocalist, singing in a doo-wop group called the Teen Kings (later the Supremes—no relation to the Motown group) for six dollars a night. Saxophonist Grover Washington Jr., a childhood friend, was a onetime member of the group. As he became a teenager, Smith began experimenting with brass instruments, including trumpet and tuba, but also began learning piano by ear.

At about 20 years old, Smith was spending hours a day at a small music store owned by a man named Art Kubera. “He said, ‘Could I ask you a question, son? …Why do you come here every day and you sit and you sit?’” Smith recalled in an interview with Jake Feinberg. “I said, ‘Well, sir, if I had an instrument, I could learn how to play it. If I could learn how to play it, I could make a living.’ So one day I went in and he closed the place up and said, ‘Follow me.’ I went with him, he opened the door of his house in the back … there was a brand new B-3 organ…. He says, ‘If you can get this out of here, it’s yours.’” For the rest of his life, Smith referred to Kubera as “my angel.”

He quickly taught himself to play the organ, listening closely to records by Jimmy Smith and showing mastery over the instrument within a year. At that point, in about 1963, he rented his organ to Brother Jack McDuff while McDuff was performing in Buffalo with alto saxophonist Lou Donaldson. McDuff let Smith sit in one night, catching the ear of Donaldson’s guitarist George Benson—who offered Smith a seat in the new band he was forming.

Smith moved to New York in 1965, still working with Benson. He recorded two albums with the guitarist for Columbia, and on the strength of those records made his own debut, Finger Lickin’ Good, in 1967. His breakthrough, however, came while freelancing at a Blue Note session with Donaldson that same year: Having finished their planned material, the band was a few minutes short of the 30-minute minimum for an LP, and filled it with an impromptu funk jam that they dubbed “Alligator Bogaloo.” It became a surprise hit, and Smith received a contract to record for Blue Note.

In 1969, Smith would have a surprise hit of his own with “Move Your Hand”—another off-the-cuff addition, this time to a live set in Atlantic City—but quickly found himself hemmed in by expectations of repetitive hits in the same mold. The hits never materialized, and Smith found financial security accompanying the likes of Marvin Gaye, Gladys Knight, and Etta James in between jazz dates that moved him into slick fusion and proto-disco territory. Finally disillusioned with the music business, Smith—with a few exceptions that were largely favors for friends—sat out the 1980s from active performance.

His career was resuscitated with the birth of acid jazz in London during the early ’90s, when Smith’s organ grooves became key sources for artists’ sampling. The same began occurring in the American hip-hop scene, with A Tribe Called Quest cribbing from his 1970 album Drives for their iconic single “Can I Kick It?” Now calling himself “Dr. Lonnie Smith,” the organist returned to jazz, this time determined to follow his own muse. This determination would define the remainder of his career, with Smith trying on multiple ideas and ensembles, including frequent work with saxophonist Javon Jackson, guitarist Peter Bernstein, and drummer Allison Miller before settling in the 2010s into a regular working trio with guitarist Jonathan Kreisberg and drummer Jamire Williams (later replaced by Johnathan Blake). His final recording, Breathe, featuring that trio along with percussionist Richard Bravo and Iggy Pop, was released in March of 2021.

A celebration of Smith’s life and