AFRO-AMERICAN MUSIC INSTITUTE CELEBRATES 36 YEARS

http://www.indiegogo.com/projects/building-today-for-tomorrow/x/267428

Pain Relief Beyond Belief

http://www.komehsaessentials.com/

PITTSBURGH JAZZ

From Blakey to Brown, Como to Costa, Eckstine to Eldridge, Galbraith to Garner, Harris to Hines, Horne to Hyman, Jamal to Jefferson, Kelly to Klook; Mancini to Marmarosa, May to Mitchell, Negri to Nestico, Parlan to Ponder, Reed to Ruther, Strayhorn to Sullivan, Turk to Turrentine, Wade to Williams… the forthcoming publication Treasury of Pittsburgh Jazz Connections by Dr. Nelson Harrison and Dr. Ralph Proctor, Jr. will document the legacy of one of the world’s greatest jazz capitals.

Do you want to know who Dizzy Gillespie idolized? Did you ever wonder who inspired Kenny Clarke and Art Blakey? Who was the pianist that mentored Monk, Bud Powell, Tad Dameron, Elmo Hope, Sarah Vaughan and Mel Torme? Who was Art Tatum’s idol and Nat Cole’s mentor? What musical quartet pioneered the concept adopted later by the Modern Jazz Quartet? Were you ever curious to know who taught saxophone to Stanley Turrentine or who taught piano to Ahmad Jamal? What community music school trained Robert McFerrin, Sr. for his history-making debut with the Metropolitan Opera? What virtually unknown pianist was a significant influence on young John Coltrane, Shirley Scott, McCoy Tyner, Bobby Timmons and Ray Bryant when he moved to Philadelphia from Pittsburgh in the 1940s? Would you be surprised to know that Erroll Garner attended classes at the Julliard School of Music in New York and was at the top of his class in writing and arranging proficiency?

Some answers can be gleaned from the postings on the Pittsburgh Jazz Network.

For almost 100 years the Pittsburgh region has been a metacenter of jazz originality that is second to no other in the history of jazz. One of the best kept secrets in jazz folklore, the Pittsburgh Jazz Legacy has heretofore remained mythical. We have dubbed it “the greatest story never told” since it has not been represented in writing before now in such a way as to be accessible to anyone seeking to know more about it. When it was happening, little did we know how priceless the memories would become when the times were gone.

Today jazz is still king in Pittsburgh, with events, performances and activities happening all the time. The Pittsburgh Jazz Network is dedicated to celebrating and showcasing the places, artists and fans that carry on the legacy of Pittsburgh's jazz heritage.

WELCOME!

Groups

Duke Ellington is first African-American and the first musician to solo on U.S. circulating coin

MARY LOU WILLIAMS

Drummer Albert ‘Tootie’ Heath Dies at 88

Drummer Albert ‘Tootie’ Heath Dies at 88

By Michael J. West I Apr. 5, 2024

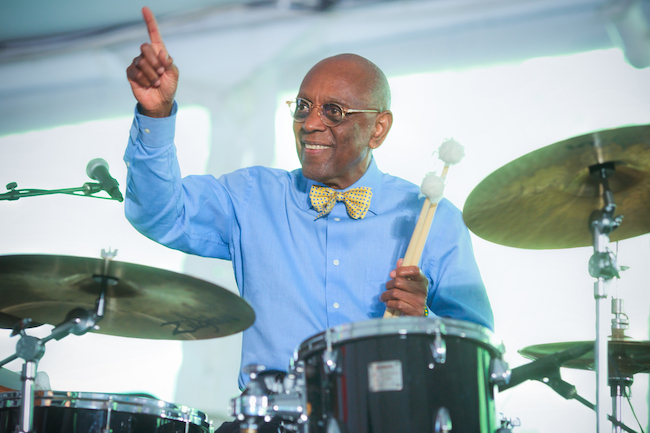

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

(Photo: Michael Jackson)Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers from Philadelphia, died April 4 at a hospital in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He was 88.

His death was first announced on social media by Jazzmobile, and was confirmed by his wife of 47 years, the former Beverly Collins Flood — who told WRTI radio in Philadelphia that the cause of death was leukemia.

Heath was also the last survivor of the Heath Brothers band, which also included bassist Percy (1923–2005) and saxophonist Jimmy (1926–2020). Though substantially younger than his siblings, Tootie cut his teeth along with them on the fecund Philadelphia jazz scene. He regularly collaborated with both Jimmy and Percy, joining them in 1975 as the Heath Brothers.

Heath cultivated a sound that was in some ways the Platonic ideal for modern jazz drumming: carefully tuned, neither overly loud nor understated, with a loose attack but tight time (positioning himself just at the leading edge of the beat) and a ride cymbal sound that was whispery and resonant. Heath followed in the tradition of his idol, Kenny Clarke. “He had a ride cymbal beat … I haven’t figured it out yet,” Heath told pianist Ethan Iverson. “When I hear it today I still say, ‘Damn, man! Is it a triplet feel or a 16th-note feel?’”

Unusually for musicians of his generation, Heath refused to lament the ways that the music had shifted from the bebop era. “I always say it kind of left the heart and went to the head,” he remarked to All About Jazz in 2015, but then added: “It’s good. There’s nothing wrong with that. It has to move. We’re sending letters from our wristwatches now. So how can we have music that’s not advanced and technical?”

Albert Heath was born May 31, 1935, in Philadelphia — the fourth child and third son of Percy Heath Sr., an auto mechanic, and Arletha Heath, a housewife. His parents were also a clarinetist and a church singer, respectively, and from birth Albert was immersed in music.

It was the examples of his older brothers, however, that directed him toward jazz. Jimmy Heath was a tenor saxophonist who played with fellow Philadelphians Benny Golson, Lee Morgan and John Coltrane. Percy Jr., the eldest brother, became a bass player after his discharge from the Tuskegee Airmen, and quickly became a major figure on the jazz scene, playing with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and co-founding the Modern Jazz Quartet in 1952.

“It seemed like my house was the capital of jazz because of Jimmy and my brother Percy,” Tootie recalled.

He started playing trombone when he was 12 but switched to drums just a few years later and soon found himself playing around town. In an NPR interview, he recalled playing in a teenage trio with alto saxophonist Sam Reed and trumpeter Ted Curson just across the street from his house.

“It must have been awful. [But] one guy came up and gave us 75 cents as a tip,” he said. “And I realized then that’s a quarter apiece — hey, man, we can get paid for doing this.”

Heath relocated to New York in 1957, and found himself in a recording studio for the first time on John Coltrane’s first session as a leader. (His second was another legend’s debut, that of Nina Simone.) He quickly became a highly regarded and much-in-demand brother, working with Mal Walrdon, Johnny Griffin and J.J. Johnson as well as his brother Jimmy. Heath was also the drummer on two classics of the early 1960s, guitarist Wes Montgomery’s The Incredible Jazz Guitar and pianist Bobby Timmons’ In Person At The Village Vanguard.

After a few years spent in Copenhagen, Denmark — where he was the house drummer for the famous Montmartre jazz club and worked regularly with fellow expatriates Ben Webster and Dexter Gordon — he returned to the United States. Heath found work with Herbie Hancock, who also appeared on Heath’s own debut album, 1969’s Kawaida, and Yusef Lateef, with whom he worked for most of the early 1970s. In 1975, Tootie, Percy and Jimmy formed the Heath Brothers (with Stanley Cowell on piano). He also became the permanent drummer for the final years of the Modern Jazz Quartet after longtime member Connie Kay died in 1994.

Still, Heath remained a freelancer for most of his career. He had a few regular employers, including trumpeter Art Farmer, pianist Tete Montoliu and his brother Jimmy, but cast his net far and wide. Collaborators through the ’70s, ’80s and ‘’90s included Anthony Braxton, Roscoe Mitchell, Pat Metheny and Jeb Patton.

Heath’s profile as a bandleader began rising in the 2010s, when he initiated a trio with pianist Ethan Iverson and bassist Ben Street. “Ethan and Ben are guys that have taken me on a little different journey,” he told All About Jazz. “It’s getting to be more and more exciting. … The three of us have found each other musically. We are exploring things that we haven’t done before.”

Heath moved to Santa Fe in 2014, living out the last decade of his life there. For more than 30 years, he was on the faculty of the Stanford University Jazz Workshop in Palo Alto, California. He was named an NEA Jazz Master in the fellows class of 2021.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his sons, Jonas Liedberg and Jens Heath; stepsons Curt Flood Jr. and Scott Flood; stepdaughters Debbie and Shelly Flood; and several grandchildren. DB

Tags:

Replies to This Discussion

© 2025 Created by Dr. Nelson Harrison.

Powered by

![]()