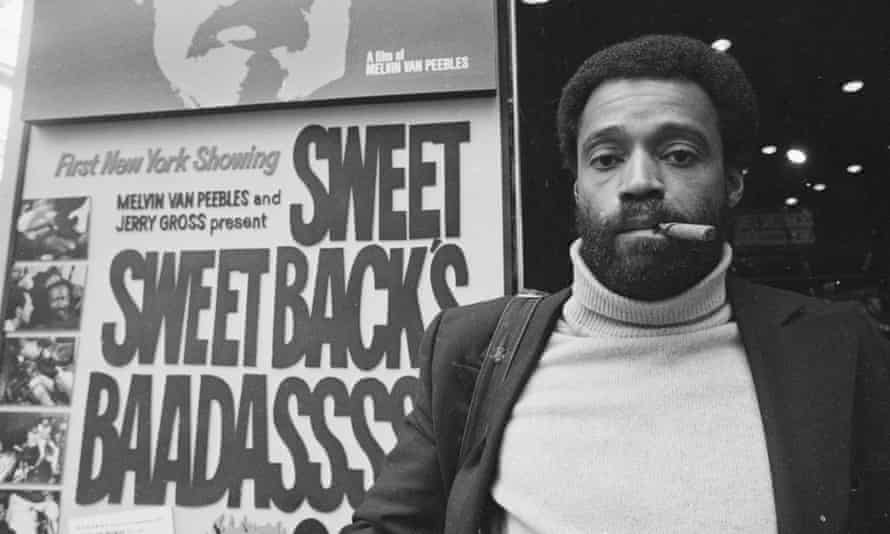

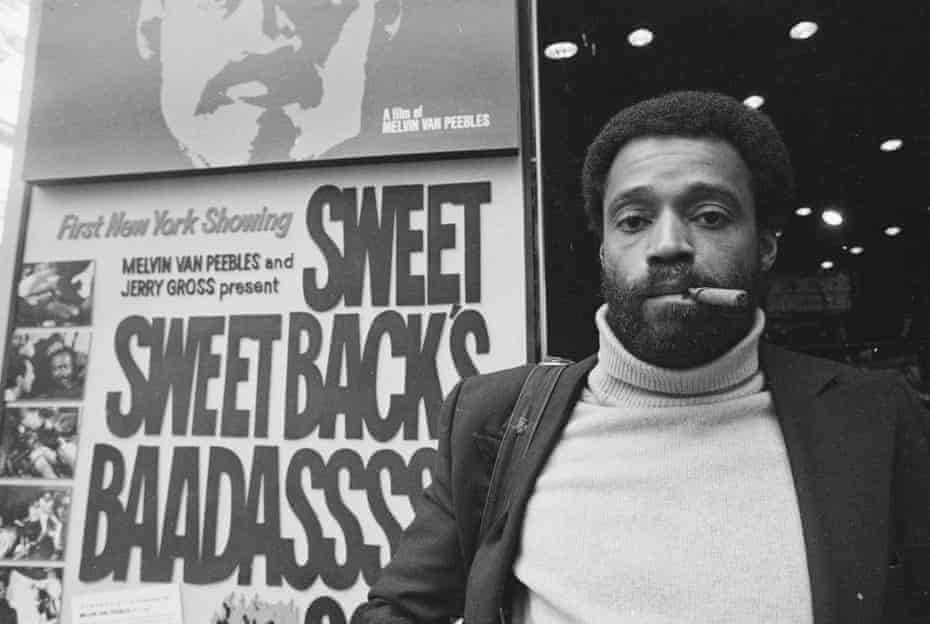

In his own words, the film-maker Melvin Van Peebles, who has died aged 89, was “the Rosa Parks of the industry”. He was one of the few African-American directors to have moved within the Hollywood studio system when, in 1970, Columbia gave him a three-picture contract. But Columbia balked at the incendiary plot of his next project, about a black hustler who kills white police officers and escapes scot-free, so Van Peebles borrowed $50,000 from the actor Bill Cosby, raised an additional $150,000, and launched an independent production as writer, director, producer, editor, composer and lead actor.

Shot guerrilla-style over 19 days, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) was a huge commercial success and effectively launched the blaxploitation genre, which gave black actors an unprecedented array of leading roles. However, Van Peebles was ambivalent about the genre, as he believed it often sidelined the political motives of his own film. It was a retaliation against Hollywood’s default modes of black characterisation: silent subservience or the stately Sidney Poitier mould. The opening sequence lists the main stars as “the black community”.

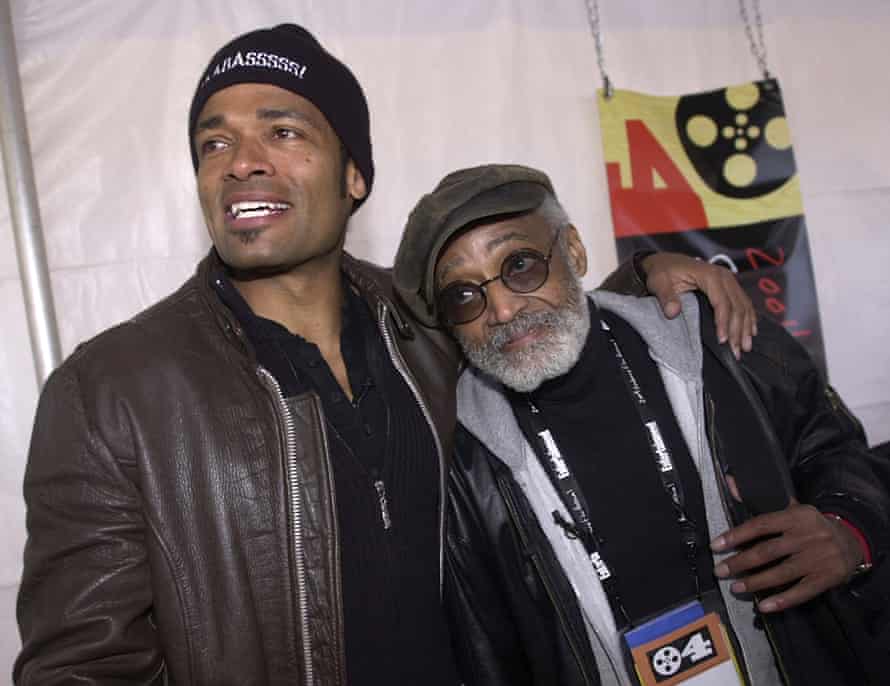

In the first scene, a boy loses his virginity to a sex worker. The child is Sweetback – played in adulthood in the rest of the film by Van Peebles, and in this prelude by Van Peebles’s 13-year-old son, Mario. (More than 30 years later, Mario directed Baadasssss!, about the making of his father’s classic, with Mario playing Melvin.) Melvin took the role of Sweetback in his own film because he claimed that no actors were interested in a character who speaks barely a dozen words (mostly expletives) and makes a living performing sexual acts.

When Sweetback witnesses the assault of a black man by racist white police officers, he attacks them and flees. The film’s most enduring images are of Van Peebles running, sporting golden flares, a billowing black shirt and a droopy moustache. The sequences are visually and sonically inventive: there are freeze-frames, psychedelic colours, superimposed images and a throbbing jazz-funk undercurrent.

When Van Peebles came to promote the film, he supplied radio stations with his own infectious musical composition. The film’s score, performed by Earth, Wind and Fire, was released by Stax Records. When the film was assigned a prohibitive X rating, Van Peebles printed T-shirts stating “Rated X by an all-white jury”, drummed up local support, had the film screened in community halls and makeshift venues, and virtually hustled it into cinemas.

He had learned the art of the hustle from his father, a tailor who ran a shop on the South Side of Chicago, where Melvin was born, the son of Marion and Edwin Peebles. (Melvin added “Van” to his name when he moved to Holland in his late 20s.) By the age of 10, he was working on the cash register in his father’s shop, and selling old clothes on the streets. He attended Thornton Township high school in Harvey, Illinois, and graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1953 with a degree in English.

He joined the US Air Force, served as a navigator and bombardier in Strategic Air Command, and married a German photographer, Maria Marx, with whom he had two sons, Mario and Max, and a daughter, Megan. A period spent working in San Francisco as a cable car operator inspired him to write the book The Big Heart (1957). He also painted and, taking inspiration from Sergei Eisenstein’s collection of essays Film Form, picked up the basics of film-making.

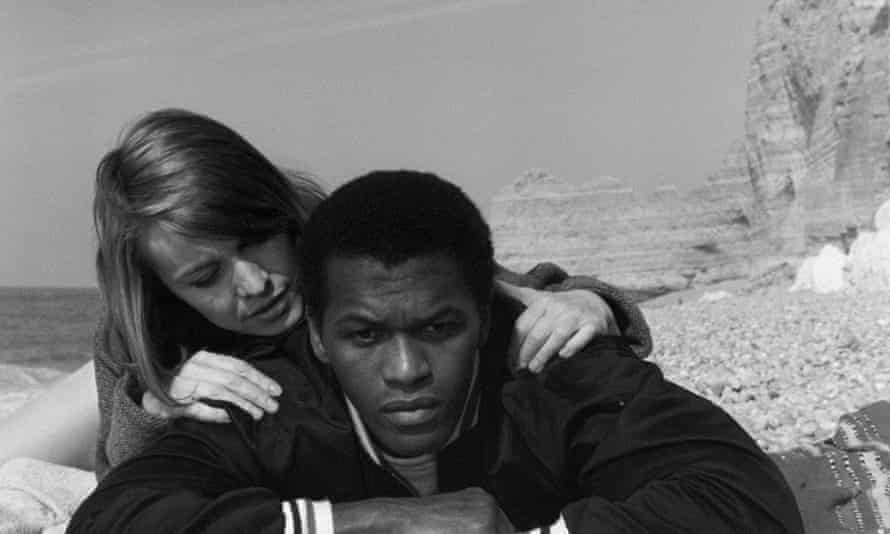

After making a series of short films, he relocated to Holland, where he studied astronomy at the University of Amsterdam. Then he settled in Paris and contributed cartoon strips to the satirical magazine Hara-Kiri. He wrote a handful of novels in French, including La Permission. His film-making was encouraged by Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Française, which had screened his shorts, and Van Peebles decided to adapt La Permission for his first feature, a French production released as The Story of a Three-Day Pass (1968).

A frank account of rank and race in the army, the film follows a black soldier stationed in France who receives a promotion and is given some time off before starting his new position. Dogged by the thought that he has become his white captain’s “Uncle Tom”, he embarks for Paris. Van Peebles shot the cafes and stalls of the Left Bank in a freewheeling documentary style. The soldier meets and dances with a white girl and arranges to spend the next day with her by the beach. There, they are spotted by three white men from the base; shocked to see the interracial couple, they report back to the captain, who swiftly demotes the soldier.

The film, punctuated by jazzy bursts of music, has more than a frisson of the French New Wave, a touch of the absurd, and the humour and jaded irony of the blues. In one of the most powerful sequences, the couple awkwardly check in to a hotel and make love in a disarming montage incorporating images of warfare, chorus lines and race demonstrations. The film won an award at the San Francisco film festival where, Van Peebles recalled with some amusement, they were surprised to discover that the Dutch-sounding director of this French production was an African American. He was then signed up to direct Watermelon Man (1970), a provocative comedy written by Herman Raucher about a racist white salesman, Jeff, who wakes up one morning to find that his skin has turned black.

The producers wanted to cast a white actor who would then appear in blackface after the transformation, but Van Peebles won the argument to use a black star (Godfrey Cambridge) who would then be done up in “whiteface”. He also altered the original ending of the film, in which the salesman woke up to find that it had all been a bad dream; Van Peebles didn’t want to equate life as an African American with a nightmare.

Although the film was made with some of his trademark experimental flourishes – including colour filters – it is essentially a broad domestic comedy, well played by Cambridge and Estelle Parsons as his long-suffering wife, Althea.

After the transformation, Jeff is met with shrieks of fear, open suspicion and hostility. If the film played America’s inequalities for laughs, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song was made in anger and defiance. Despite proving Van Peebles’s box-office clout – Sweetback made more than $10m in 1971 – it lost him his deal with Columbia and won him a reputation as a volatile talent.

By then, Van Peebles had achieved success as a musician, for his albums of original, proto-rap material including Brer Soul (1968). He then turned his attention to Broadway, writing the music, book and lyrics for a “ghetto-life” musical, Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death, which opened in October 1971 and ran for more than nine months. Before it closed, he opened another musical on Broadway, Don’t Play Us Cheap! Its book received a Tony nomination and a film version came out in 1972. In 1974, he released a new album, What the … You Mean I Can’t Sing?, its title reflecting his gruff humour and a progression in his vocal delivery from the spoken lyrics on previous releases.

Ten years passed before he released another album or film, but Van Peebles kept busy in the theatre. An autobiographical picaresque musical, Waltz of the Stork, opened in New York in 1982, with him as its star, and a couple of years later he directed a revamped puppet version of the show. The material was recycled into a 2008 film, Confessions of a Ex-Doofus Itchy-Footed Mutha, and a graphic novel.

By 1983, Van Peebles had developed his most unexpected role yet, moving from Broadway to Wall Street, and becoming a trader on the floor of the American stock exchange. In 1986, he wrote a book for aspiring investors, Bold Money: A New Way to Play the Options Market.

Meanwhile, he returned to movies. He had a role in Robert Altman’s OC and Stiggs (1985) and appeared with Mario in Jaws: The Revenge (1987), the TV series Sonny Spoon and the predominantly African-American western Posse (1993), which Mario directed.

Back in 1971, Huey Newton had praised Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and made it mandatory viewing for the Black Panthers. In 1995, Van Peebles adapted his own novel about the formation of Newton’s radical party for the film Panther, directed by Mario. The following year, they made Gang in Blue, about racism within the police.

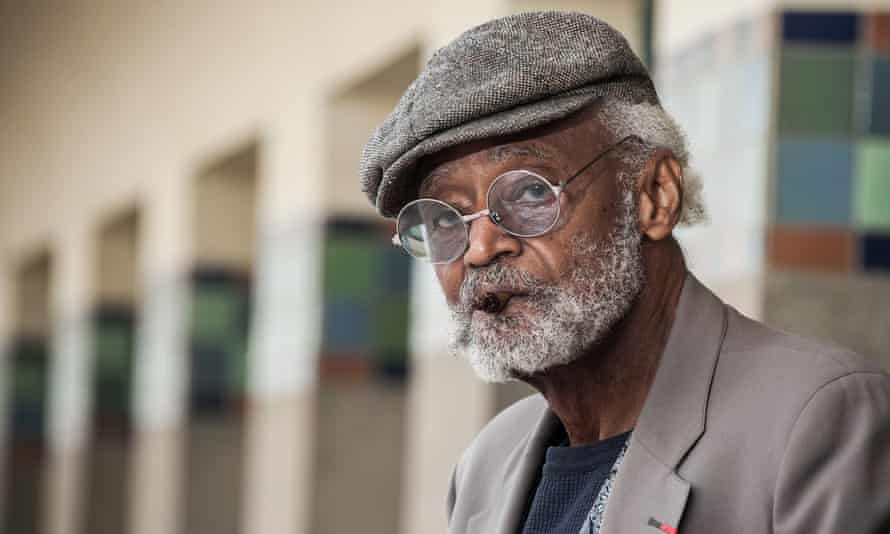

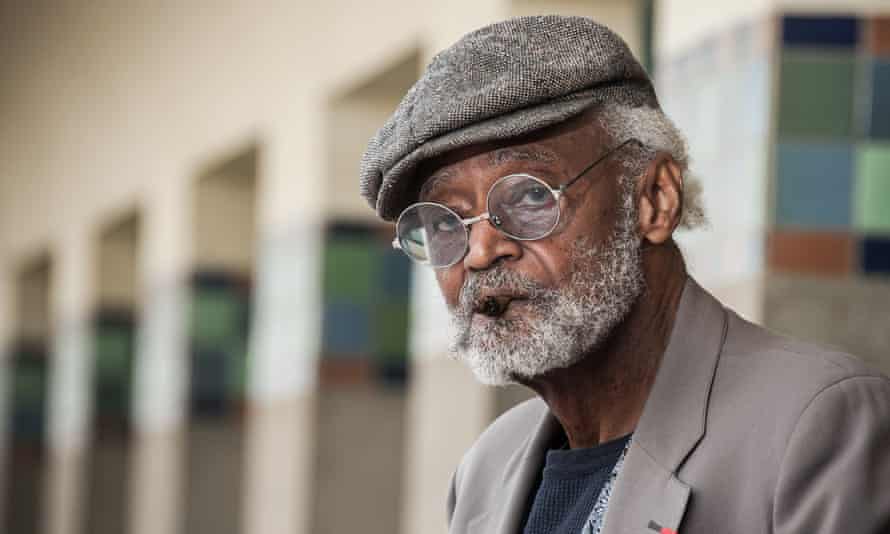

In 1998, Van Peebles wrote and narrated the documentary Classified X, an overview of black characters in American film. Routinely dubbed the godfather of black cinema – although he preferred “godfather of independent cinema” – he increasingly appeared in documentaries, usually wearing his trademark round glasses and beret, chewing on a cigar. His projects became riffs on past achievements: he and Mario published a book about working together, No Identity Crisis (1990), and appeared in The Hebrew Hammer (2003), an irreverent Jewish take on blaxploitation.

He made another French production, Le Conte du Ventre Plein (Bellyful, 2000), released shortly after he was named a chevalier of the Légion d’honneur. He also launched a musical-theatre version of Sweetback in France in 2010.

His son Mario cast him in small roles in Redemption Road (2010), We the Party (2012) and Armed (2018), and he also appeared in Tina Gordon’s family comedy Peeples (2013).

His marriage to Maria ended in divorce in 2018. Megan died in 2006. He is survived by Mario and Max, another daughter, Marguerite, and 11 grandchildren.

Melvin Van Peebles (Melvin Peebles), film-maker, novelist and musician, born 21 August 1932; died 21 September 2021