Mike Longo, who led a distinguished jazz career as a pianist, composer and educator, notably as longtime musical director for Dizzy Gillespie, died on Sunday at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. He was 83 and lived in New York.

The cause was COVID-19, confirmed Dorothy Longo, his wife of 32 years.

She said Longo was admitted to the hospital early Tuesday morning, and had preexisting medical conditions.

Longo is not the first jazz casualty of the coronavirus — that tragic distinction belongs to Argentine saxophonist Marcelo Peralta, who died in Madrid on March 10 — but his prominent stature and breadth of associations bring the tragedy much closer to home for the jazz community in New York.

“He was a consummate musician, a dedicated musician and instructor,” says bassist Paul West, whose close musical association with Longo started in 1968, when both were members of Gillespie’s working band.

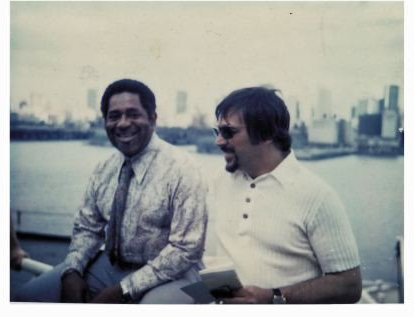

Longo served as musical director of that band, which had a front line of Gillespie on trumpet and James Moody on saxophones and flute, from the late 1960s through the first half of the ‘70s, and intermittently for more than a decade after that. He appears on Gillespie’s live Impulse! album Swing Low, Sweet Cadillac, and several others, including Portrait of Jenny. Here is footage of the band from a concert in Copenhagen in ’68, playing a Longo original called “Ding-a-Ling.”

Longo had an extensive solo career as well, both in the swinging modern-jazz mainstream and in a funkier mode, on albums like The Awakening, released on the Mainstream label in 1972. Reviewing one of his early forays as a bandleader the following year, New York Times critic John S. Wilson observed that an acoustic trio format gave him room for shading and subtlety. “But whether he is playing blues, a Latin tempo or a ballad, there is always a compelling rhythmic sense underlying his attractive improvisations,” Wilson added.

Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on March 19, 1937, Michael Joseph Longo entered a musical family: his father was a bassist, and his mother played organ in church. He was barely past toddler age when he took up the piano; at four, he began studying with a teacher at the Cincinnati Conservatory.

Soon thereafter his family moved to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where he eventually played his first gigs in his father’s dance band, at 15. Around the same time, he attended a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert featuring virtuoso pianist Oscar Peterson, who instantly became a hero.

Years later, in his early 20s, Longo studied for six months at the Advanced School of Contemporary Music, which Peterson had established in Toronto; he later recalled this as “the most intense experience in my life, musically speaking.” What he learned from Peterson, he added in an interview with All About Jazz, was nothing less than “how to be a jazz pianist — textures, voicings, touch, time conception, tone on the instrument.”

But Longo was no slouch even in his teens, when his playing caught the ear of alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, who was then band director at Dillard High School in Fort Lauderdale. Adderley became a mentor and a source of work; when his regular pianist couldn’t make a gig at Porky’s, the Miami-area strip joint later immortalized in a 1980s teen romp, he asked Longo to fill in. (After securing his mother’s permission, he did. It was his first booking in a club.)

After earning a degree in classical piano at Western Kentucky State University, Longo began his jazz career in earnest, working with saxophonist and big band leader Hal McIntyre, Nashville guitar ace Hank Garland and others. Soon after he moved to New York City, he found steady work at the Metropole, playing traditional jazz with the likes of trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen.

Longo was working at the Embers West in Midtown Manhattan, as part of a house rhythm section, when Gillespie heard and promptly hired him. The depth of that association extended well beyond Longo’s tenure in the band; in 1980 he composed an orchestral piece called A World of Gillespie, which was first performed in New York by the Henry Street Settlement Symphony Orchestra, and then by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. (Gillespie was the soloist.)

West performed often in a duo or trio setting with Longo, especially in recent years. “We depended on each other, so to speak,” West says. “He depended on me to be supportive and in tune with his playing. So we played as if one person was playing two instruments.”

In addition to his wife, Longo is survived by his sister, Ellen Cohen, and many cousins, nieces, and nephews.

If Longo had a flagship group, it was the 18-piece New York State of the Art Jazz Ensemble, which released a studio album called Explosion in 1999. The band was active as recently as March 10, when it performed in the John Birks Gillespie Auditorium at the New York City Baha’i Center.

The Baha’i faith was another commonality between Longo and Gillespie, and a source of deep simpatico. “I would say that the Baha’i faith was his moral and musical compass,” said Dorothy Longo, who has been in self-quarantine in her husband's apartment on Riverside Drive, after testing positive for the coronavirus herself.

“Because,” she went on, “the Baha’i faith promotes the unity of humankind.”