When Jamila Wignot was a sophomore at Wellesley College, the Black student group on campus scored tickets to the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Wignot had no expectations. A financial aid kid, she was just grateful for the night out.

But as Ailey’s dancers defied gravity, she felt herself lean in, transfixed by the drama of everyday life captured through their movements.

“I just remember my feeling of the evening,” she told the Guardian. “The kind of searching and reaching. And a kind of counter-narrative, you know, that was important to me at that time.”

More than two decades later, Wignot is the director of Ailey, a documentary portrait that profiles the defining figure whose company sparked her love of dance. To fans, the name Alvin Ailey is synonymous with incisive choreography that celebrates the Black community in America. But Wignot delves deeper to unmask Ailey as a gay Black man with a tumultuous life outside of his beloved works.

What emerges is a towering figure who won worldwide acclaim with art steeped in personal experience, yet was too afraid to openly share his full identity even in death.

“I think he’s a reflection of, you know, someone who is living, who is trying to find a way to express himself in all ways but is also very constrained by the times in which he lived,” Wignot said.

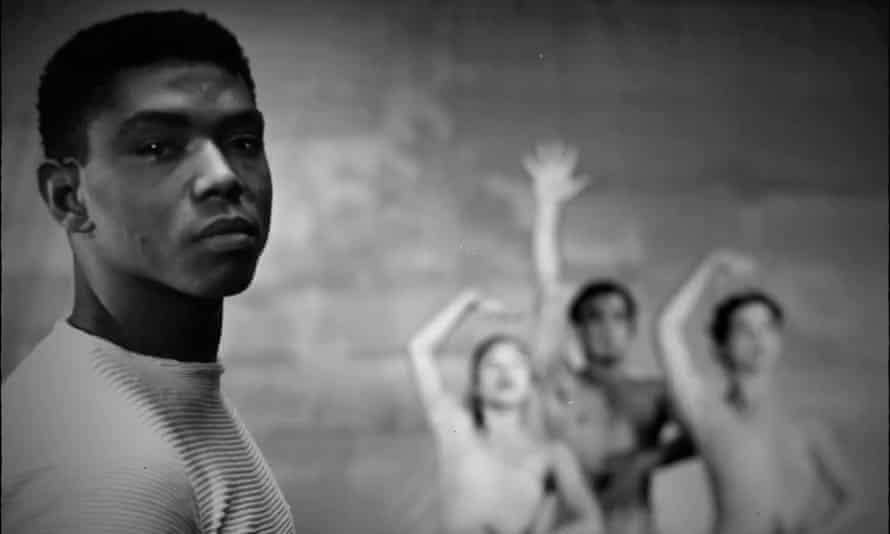

Ailey portrays its namesake through the words of his confidants, contemporaries and artistic descendants, including those who have devoted their lives to preserving and bolstering his legacy. The film occasionally flashes forward to present-day rehearsals, as choreographer Rennie Harris guides Ailey dancers through Lazarus, a 2018 homage to their company’s founder. Those scenes act as a reminder that in some ways, Ailey is reborn every time his visionary ensemble steps onstage.

But while Wignot establishes Ailey as a legend from the outset, she also wastes no time before tackling the more complicated layers of his humanity, beyond his many achievements and accolades.

The narrative takes shape through a chorus of dancers, childhood friends and fellow artists, including Ailey’s successor as artistic director, Judith Jamison, former executive director Bill Hammond and famed choreographer Bill T Jones. Their memories exude love, admiration and loyalty, but also sadness and compassion for their colleague. At times, Wignot said Ailey’s devoted collaborators hesitated to share some of the more traumatic details from his life. She understood their misgivings.

“How do you respect someone’s privacy when they’re no longer around to tell you what they would want or wouldn’t want?” she said.

So she turned directly to the source, mining an extensive collection of audio tapes and public interviews to pull insights that Ailey willingly shared in life. Those first-hand recollections give him agency and autonomy to tell his own story, even in his darkest moments. “He didn’t himself shy away from a very vivid description of kind of this unraveling that was happening for him,” Wignot said.

Ailey spent his early childhood in Texas during the Great Depression and Jim Crow era, a formative origin that inspired some of his most iconic creations. He discovered dance after moving to Los Angeles but didn’t fully commit to the art form at first.

To Wignot, that was Ailey’s story of becoming. Even as dance drew him in, he hesitated. But when he eventually surrendered, it became his means of self-expression. “I don’t think you can understand Mr Ailey’s artwork if you don’t understand the roots of where he came from and the experiences that he was having,” Wignot said.

“You can see in the dance footage we show of him. Like, what he is pouring out of himself I think has to do with every part of his identity.”

In the 1950s, Ailey relocated to New York and founded the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. By 1960, he premiered Revelations, his 36-minute pièce de résistance celebrating Black heritage that’s now the most widely viewed modern dance work anywhere. With scores of high-profile performances and international tours, Ailey’s troupe became a “cultural ambassador to the world”. But even as he and his dancers succeeded professionally, his personal life collapsed.

In Wignot’s retelling, Ailey comes off as a solitary artist married to his craft. She zeroes in on the insecurity that plagued Ailey’s career and made him question his own worthiness, as well as a debilitating mental health crisis that terrified the people close to him.

Although he dated intermittently, he couldn’t find long-term companionship while trying to conceal his sexuality from much of the world. And when he died in 1989, amid the Aids epidemic, he hid his Aids-related illness. His doctor instead blamed his demise on a rare blood disease.

He’s “a public figure, who can’t live out all of himself in public”, Wignot said.

Yet as Wignot studied Ailey, she uncovered a man who was defined by much more than adversities and secrets. He was generous and selfless. He used his platform to depict a thriving Black life that exists beyond brutality, violence and daily oppression.

Part of why Wignot made Ailey now was because of how strongly that message still resonates. “Films about beauty and joy,” she said, “and artists who are in search of, you know, some way of showcasing, you know, human capacity for love, and joy, and possibility – that all feels, you know, like something we have to be reminded of.”

Ailey is now out in New York cinemas and will open on 30 July in Los Angeles and on 6 August nationwide with a UK date to be announced

You need to be a member of Pittsburgh Jazz Network to add comments!

Join Pittsburgh Jazz Network