On a Friday afternoon in April, David Lyttle pieced together his drum kit on a patch of grass in Pittsburgh’s Hill District.

“I wish I could say this is a really unusual set up for me, but it’s not really,” he said. “We’ve done this in the desert, in front of some mobile homes, a truck stop.”

For the past month, Lyttle has been away from his hometown in Northern Ireland for a residency traveling across the U.S. He’s playing at both unexpected places and significant landmarks. The Hill House Association helped him coordinate a performance on the lot where jazz great Art Blakey's childhood home once stood. Blakey is Lyttle's musical inspiration.

Lyttle’s friend, saxophone player Tom Harrison, is joining him for a portion of his trip.

For the low-key performance, the two prepared a medley of some of Blakey’s greatest hits.

Hill District natives Charles Paris and Lance Hicks pulled over in their black pickup truck, after hearing the music. Lyttle had a few questions for them.

“Art Blakey is my hero and the reason I became a jazz drummer," Lyttle said. "How known or respected is he now here in the Hill District? Do people know his name?”

“Oh yeah,” Paris said, “the older generation do. Younger generation, it’s just Play Station, and all that now.”

Paris said when he was growing up, he used to sneak into jazz clubs to hear the music, and lots of his friends played instruments.

“There’s none of that anymore,” he said. “Kids don’t even like your drum sets. There was a lot of guys coming up playing that.”

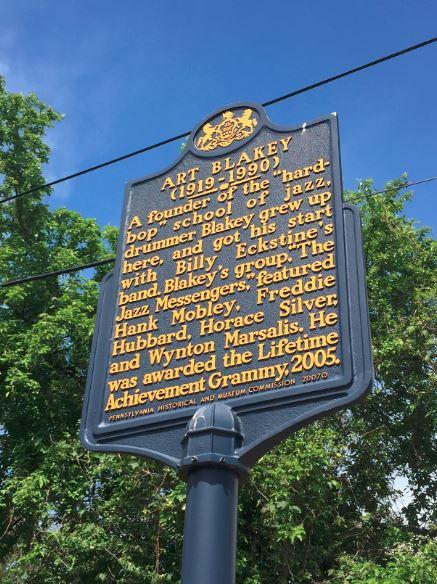

Hicks said it’s hard to maintain that history. All that marks the vacant lot is a plaque on a pole.

“If they didn’t post these monuments of historical buildings, you would never know they existed,” he said.

Bob Studebaker, a longtime jazz DJ and producer of 90.5 WESA's Jazzworks, said it’s not unusual for lifelong Pittsburghers to be unaware of these cultural important locations.

“It’s hard to imagine now, but [jazz] was cutting edge and radically new more than 100 years ago,” he said.

At the turn of the century, Pittsburgh was a destination for jazz, especially in the Hill District.

“It’s where the concentration of African Americans were in the beginning when jazz first came to Pittsburgh in the early 1900s, by a guy who was kind of a Johnny Appleseed of jazz,” Studebaker said.

Fate Marable came to Pittsburgh by riverboat, which is largely how jazz got out of New Orleans.

In the 1920s, Pittsburgh was located along the rail line between New York and Chicago. Studebaker said musicians would stop because there were places to play, and a lively audience. He said it was a nexus for the genre.

“Pretty much every time jazz moved into a new direction, it was a Pittsburgh artist who was being the catalyst for the evolution,” Studebaker said.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, that direction was bebop, which moved jazz out of the swing era.

Musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk played the style.

“A Pittsburgher, Mary Lou Williams, is known by jazz historians as the mother of bebop,” Studebaker said. “She was the mentor to these young musicians. She was an established star with highly respected skills and innovative ability.”

Studebaker said Art Blakey was the one who took the signature drumming style of bebop in the 1940s and refined it.

At the end of the 1940s, Blakey put together a band that would evolve over decades—the Jazz Messengers. Blakey and the group’s pianist Horace Silver originated hard bop.

“Hard bop just slowed it down a little bit. It was a less frenetic pace, it had a more soulful quality, which came from the influence of a gospel feel,” Studebaker said.

Blakey played at the many clubs along Crawford Street and Wylie Avenue.

“The Hill continued to be a Mecca for jazz until 1968,” Studebaker said. “That’s when a lot of American cities changed, when there were riots everywhere, and the economic vitality of the Hill was pretty much stripped away.”

But the history remains, which is what continues to draw people from all over the world.

“Almost universally jazz musicians feel a reverence for the people who invented the music," Studebaker said. "Musicians all over the world know Pittsburgh's Hill District because that’s where Art Blakey came from. That's where Billy Strayhorn came from, Ray Brown." (Billy Strayhorn came from Homewood/East Liberty actually)

David Lyttle is here is to pay tribute to the greats, but he’s also popping up and surprising people with his music to see how receptive they are, since he fears a dwindling audience for the music he loves.

“People just have lost willingness to go check stuff out. Maybe the internet has killed that curiosity, because on demand you can get whatever you want musically,” he said. “You sit around and wait to be recommended something, rather than talking to your friends or checking out a concert.”

He said musicians need to be more proactive about engaging audiences, and breaking down barriers, especially to jazz, which he says can be misunderstood. He said in that, his residency has been a success.

“I’ve learned that most people are pretty open-minded whenever they actually hear the music, but it’s getting them to come out,” Lyttle said.

Studebaker said if you play it they will come. He said the Pittsburgh jazz scene is still putting out great musicians, but there’s less of a live music culture, aside from the great Roger Humphries, a contemporary drummer, and his weekly jam sessions. For Studebaker, it’ll be up to organizations like the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, and its annual jazz festival, to keep the music going -- and accessible.

You need to be a member of Pittsburgh Jazz Network to add comments!

Join Pittsburgh Jazz Network