Carl McVicker strode to the podium of his music class at Westinghouse High School and studied the faces of his students. It was the first day of the school year, and he recited the same introduction that he would give students for more than three decades.

“I don’t care what religion you are, what sex or what race,” he said. “It’s how you blow the horn that counts with me.”

Twenty-five years after his death, the legacy of this teaching legend endures.

Four of his students — pianists Ahmad Jamal, Billy Strayhorn, Mary Lou Williams and Erroll Garner — have been inducted into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame. New York Times music critic Robert Sherman called another student, Dakota Staton, “one of America’s great vocal stylists.” Four more students — Nelson Harrison, Grover Mitchell, Wyatt Ruther and Art Nance — played in The Count Basie Orchestra, which Mr. Mitchell also conducted.

“Obviously, there are teachers who have influence on producing quality students but not to that degree,” said Mary Lynne Bennett, an adjunct professor of piano at Duquesne University and president of the executive committee of the Pennsylvania Music Teachers Association. “The high level of recognition his students have achieved and the number of students who have achieved it is a rare combination.”

Whether his students achieved fame or their musical interest waned, their teacher had one name – Mr. Mac.

• • •

Carl McVicker was born in 1904 in Morris Township, Greene County, to a musical family. His father, a Presbyterian minister, played the flute; his mother, the piano; and his sisters, the violin. Mr. Mac mastered the trumpet. He graduated from what are now Edinboro University of Pennsylvania and Carnegie Mellon University.

He played with bands at the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island in Michigan, in Chicago, on an ocean liner and in Europe. His parents sometimes went into “hysterics” over the music he performed. Once, while practicing triple tone solos at home, his father said, “I never want to hear you play something like that again on Sunday.” He disdained “dance music.”

Mr. Mac’s girlfriend Ella refused to travel, ending any of his professional aspirations. They were married in 1931, four years after he began teaching at Westinghouse.

• • •

Nearly a century ago, about 400 students, only 20 percent of whom were black, attended Westinghouse. Many of the black and Italian families near Homewood treasured music and provided private lessons before the youngsters reached the high school.

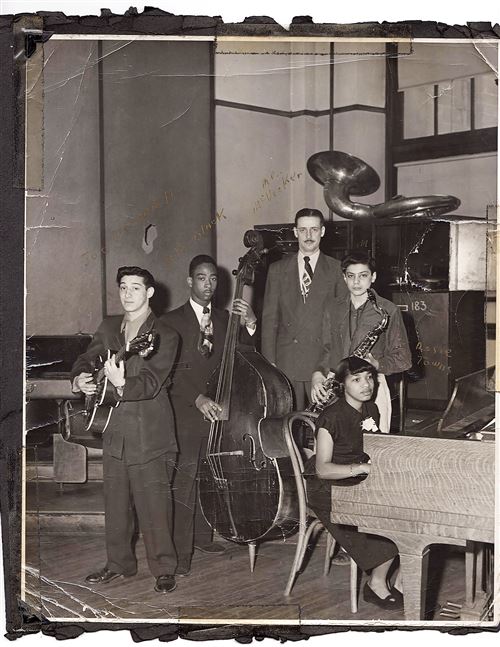

Mr. Mac, director of orchestras and bands, stressed the fundamentals but is noted for introducing jazz, then considered speakeasy music, to high school. In about 1946, he launched the K-dets swing band.

Standing about 6-foot-2 and wearing a suit, tie and distinguished mustache, Mr. Mac loomed large to students. Unlike many teachers then, he brandished no paddle.

“Some people are born to teach, and he was one of those people,” said his son, Carl McVicker Jr., 80, of Naples, Fla. His father taught him to play the trumpet, but Carl Jr. switched to bass and played in the Johnny Costa Trio on “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.”

Mr. Mac’s students loved him, and he loved them. He never exhibited anger but could show other emotions.

“More than once I saw him moved to tears by a student’s accomplishment,” wrote former student Patricia Prattis Jennings of Rosslyn Farms. She was concertmistress and first piano at Westinghouse.

A student’s inattention could make Mr. Mac walk into the hallway, crying, recalled Mr. Harrison.

“If we weren’t into wanting to play, it really hurt him because he gave his all,” said Mr. Harrison, 77, of Shadyside, a brass player. “I would go back into the hallway and talk him back in.”

Frank Cunimondo, 84, of Natrona Heights played lead saxophone and piano at Westinghouse. In his oral history at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, he said Mr. Mac “had the ability to bring out the best in people, and he made you take pride in what you did, pride in being a musician.”

Former student Neil Dorsey admired Mr. Mac’s compassion for students too nervous to play in front of classmates during tests.

In his oral history, he recalled Mr. Mac saying, “‘Don’t worry about not being able to make music. I can see you know what you’re doing by the movement of your fingers.’”

Sure enough, music eventually would come from the shy student’s instrument.

• • •

One of his favorite students, Mr. Garner, could hear a song once and play it back on the piano by ear. He also played tuba in the marching band.

The band was rehearsing for a variety show, and the piano player was having a hard time with the transitions. A band member suggested letting Mr. Garner, who was sitting in the back and listening, try the piece.

“What’s the use,” Mr. Mac answered. “He can’t read music.”

The band member insisted, and the teacher relented. The prodigy played the piece flawlessly, and the band applauded wildly.

Afterward, Mr. Mac said, “Erroll, I don’t care whether you can read music or not. You own this band from now on.”

Mr. Garner frequently cut his academic classes and hid behind the risers in the band room to spy on Mr. Mac’s music class. Halfway through, Mr. Mac could see his head poking up among the seats. The principal eventually asked the teacher if he would allow the youth to spend half the day in his classes.

“Sure, it won’t bother me,” Mr. Mac said, according to the Erroll Garner Archive at the University of Pittsburgh. “You almost had to lasso him to get him off the piano stool.”

• • •

Mr. Mac was known mostly for producing jazz artists, but his former students also performed for big-city orchestras. Two of them, Ms. Jennings and Paul Ross, were the first black musicians hired by the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in the mid-1960s.

In 1956, Westinghouse won the state orchestra championship. A dejected teacher from York whose orchestra had won the title in previous years said, “Let’s get the hell out of here. No wonder that orchestra won. They all take lessons from the Pittsburgh Symphony.”

Mr. Mac turned around and said, “Mister, I’ve got news for you. None of my people can afford to take lessons from the Pittsburgh Symphony. None.”

He added, “My kids were lucky to have enough to eat.”

• • •

Despite his singular role in music education, his record bears a stain that haunted him to his grave.

In 1936, the principal of Westinghouse, fearing the school might have its second black valedictorian in three years, told staff to lower the grade of Fannetta Nelson Gordon. Mr. Mac reluctantly changed her A in music to a B.

The erasure on her transcript still showed 75 years later. The Westinghouse Alumni Association recognized Mrs. Nelson Gordon as valedictorian in 2011, three years after her death. Sophia Phillips Nelson, her sister and the first black valedictorian of Westinghouse, accepted the award for her.

Mr. Mac tearfully admitted changing the grade to Mr. Harrison, her nephew, because the principal threatened his job.

“I knew that wasn’t where his heart was,” Mr. Harrison said. The teacher wanted to apologize to Mrs. Nelson Gordon but died before he could do so.

• • •

Carl McVicker retired from Pittsburgh Public Schools in 1961 after 34 years at Westinghouse. His students, however, remembered him long after their graduation.

Mr. Garner arranged for Mr. Mac to sit at a front table during his concerts in Pittsburgh. At a concert at Carnegie Music Hall in Oakland, Mr. Mac led the nearly blind mother of Mr. Garner up the steps to his dressing room.

Warren Watson, 95, of Schenley Heights called Mr. Mac after his retirement to tell him how much he enjoyed playing trumpet at Westinghouse. Mr. Watson, who later led a band in the Navy and became a judge in Allegheny County, reminisced about high school with a laugh. “I carried my books sometime, but I always carried my trumpet.”

Decades later, Mr. Mac was unanimously inducted into the Westinghouse Wall of Fame honoring alumni who achieved notable success. Because he did not graduate from the school, he became its first honorary inductee, his photograph surrounded by his students who became stars.

"All the great music, the talent came from God, but the encouragement and the confidence to get out there and make it came from Mr. McVicker," said Valeria Williams-Bullock, founder of the Wall of Fame.

In the early ’90s, Mr. Mac’s health began to fail. Mr. Harrison visited him in the hospital and heard that he sometimes conducted music, probably played on the radio, from his bed.

He died in 1993 at the age of 89. Though the music he taught was lush, a simple bronze plaque, noting just his name and the dates of his birth and death, marks the site at Woodlawn Cemetery in Wilkinsburg where he and his wife were laid to rest.

Former student Danny Constable, known as Danny Conn when he backed up Stevie Wonder, the Supremes and Frank Sinatra, performed a bluesy tribute at his mentor’s funeral. Mr. Conn, the foremost jazz trumpeter to hail from Pittsburgh, routinely came back to Mr. Mac’s grave, until his own death in 2006, to serenade the man who helped mold him.

In those visits to his father’s grave, Carl Jr. imagines that the trumpeter played the same rousing fight song that he performed at Mr. Mac’s funeral.

“Westinghouse Forever.”

Bill Zlatos (billzlatos@gmail.com) is a freelance writer living in Ross.

You need to be a member of Pittsburgh Jazz Network to add comments!

Join Pittsburgh Jazz Network